"News with equal focus on each person"

| 4 May 2005 | Archive | Subscribe for free by E-mail

or |

|

Prostitution In IndiaBy F. Merlin FlowerShe can be found waiting under a tree at the bus stop, railway station, or any busy place. She stares directly into the eyes for any sign. A slight response and she flashes a welcome smile, a familiar picture of prostitutes in India. According to an International Labour Organization estimate, India has 2.3 million prostitutes. An oft repeated cause of prostitution is poverty. "But poverty is only one of the reasons," said J. Helen of Swathi Mahila Sangha, a non-profit organisation in Bangalore. She said that the helplessness of women forces them to sell their bodies. Ratna, a sexual worker in Bangalore, is an example. Her parents' death left her with no guardians, forcing her into prostitution as a job to keep her "soul and body together." Many girls from villages are trapped for the trade in the pretext of love and elope from home only to find themselves sold in the city to pimps who take money from the women as commission. Ratna is controlled by a pimp. At the bus stand it is he who brings the customer to Ratna. He said that he gives concessional rates to regular customers. But Kirthana said that she became a sex worker to get more money. She said that she would do everything possible to keep her profession a secret from her parents. Helen accepted that most of the close kin of these workers do not know that they are sex workers. Prostitution is still a crime in India, and society looks down upon prostitutes. Voluntary groups have demanded legalisation of prostitution. "It is their work. If people can sell kidney and blood, why not their bodies?" asks Helen. Since prostitution is not legal, the police can arrest sex workers at any time. Shabnam, another sexual worker in Bangalore, said police arrested them any time they wished. Shabnam had been tortured naked and sexually assaulted by the protectors of justice. The police, whose main function is to protect and serve, turned out to be robbers stealing the little money that these workers had "earned." To protest against this kind of violence, Bangalore non-profit organisations, under the banner of Mahila Ookoota, held a protest rally on November 28, 2004. Roshan, the field officer of Sangama Foundation, a Bangalore non-profit organisation, said that torture had decreased "a bit" after the rally. One of the inspectors accused of torture has been transferred. Helen also said that now the police take sex workers to court directly rather than keeping them jailed. But Ratna wasn't really worried about the police. She said that they let her out after she pays a fine of Rs. 200 (about US$4.60). She gets about Rs. 100-200 per customer. The only thing which bothered her was her son Raghu. She wants him to be in safe hands. But almost all the sex workers spoken to at the bus stand except Ratna said they do not want to be in a hostel. Most ashrams (religious institutions) are viewed with skepticism by sexual workers. This is due to the rumour that children of sex workers are sold abroad under the guise of adoption. Ratna said that she would stay in a hostel for the sake of her son, though she didn't believe in religious social workers. Her fear for her son is justified, as children of sex workers often end up in the same profession (with boys as pimps). It does take a lot of counseling to bring changes in a sex worker, held Helen. They arranged alternative jobs for sex workers who wanted them. Kirthana said she hardly went to hospitals and was "very healthy." She said she hadn’t gotten any diseases due to her work. "There is awareness on the use of condoms," said Helen, "and most of the customers themselves are responsible for this." Helen said their organization, after counseling sex workers, does nudge them to take a blood test to be on the safer side. Many transsexuals, called hijiras, are sex workers. The families of hijiras reject them. They face opposition from the public, and with the denial of employment they take to begging and then enter the sex market, said Roshan. There are hamams (bath houses) where these transsexuals live together. Castration is performed by the men themselves, who feel that they are "women trapped in a male body," said Roshan, a "feeling which gets stronger with time." Both police and thugs torture hijiras. One victim was Kokila, a 21-year old transsexual prostitute. She was raped by 10 thugs on 18 June 2004. The thugs ran off after two police approached, although two were caught. But police did not lodge a complaint as she asked, and instead harassed her both physically and mentally by using abusive language. She was kept naked for seven hours and was not given water. Even after the arrival of the inspector the torture continued. They tried to force Kokila to confess robbing a diamond ring. She refused, and they took her to two hamams and searched them illegally. They made her wear shirt and pants. Police left her home at 3:30 am. A complaint was registered the next day. Roshan said the case is still in court. Rathna doesn't know the name of even a minister (besides the Chief Minister) in the state. "This is because they are led to feel like aliens in their own land, and most of them have a detached view of their society," said Helen. The solution, according to Helen, is to legalize prostitution in India to help the prostitutes live as human beings instead of just living things. How was this story's length set? A letter to the editor, on a program to help Indian prostitutes |

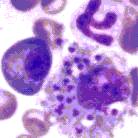

Drug Company To The PoorBy Larry Baum Leishmaniasis parasite

Only 3% of the research and development spending of the drug industry is targeted toward diseases of the developing countries, where 90% of people live. Victoria Hale, a drug industry scientist, launched the non-profit Institute for OneWorld Health in 2000 to close that gap by bridging the divide between commercial pharmaceutical companies and academic research institutes. The institute convinces high-profile organisations to donate intellectual property rights to drugs against diseases affecting the developing world. Celera Genomics and Yale University have each donated rights to promising compounds for the treatment of Chagas disease, and the University of California, Santa Barbara has given rights to a potential treatment for schistosomiasis. Now, it is close to one of its biggest successes—developing a cheap antibiotic for visceral leishmaniasis, a parasitic infection transmitted by sand fly bites that affects 1.5 million and kills 200,000 a year. To treat visceral leishmaniasis, the standard regimen using amphotericin costs US$120, but treatment with the antibiotic drug paromomycin would only cost US$10, a critical difference that could make treatment affordable to hundreds of thousands. The World Health Organization (WHO) had conducted small trials showing paromomycin's effectiveness, but couldn't find a sponsor for a large trial to compare the drug against amphotericin. In 2001, WHO agreed to hand over the trial to the institute, which arranged funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The results, presented in April, showed that paromomycin is about as effective as amphotericin. The institute will apply to India for regulatory approval. The institute has now set its sights on a treatment for diarrhoea, which kills two million people each year, most of them children, by dehydrating them. The strategy is to screen compounds that might prevent dehydration by stopping release of water into the intestines. The Lehman Brothers Foundation is providing the money. Sources: SciDev.net and The Economist How was this story's length set? Slipping On The World's New Year Resolutions For The MilleniumBy The World BankIn 2000, world leaders made resolutions for the new millenium, goals to be achieved by 2015 to improve life for the poor: halve the number of people living on less than one dollar a day, halve the number of global poor living in hunger, ensure all children complete primary education, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce by two-thirds child mortality, improve maternal health, and more. Five years after the Millennium Declaration, many countries have made progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), but many more lag behind. Faster progress is needed in reducing maternal and child deaths, and boosting primary school enrolments, according to the World Bank’s report, World Development Indicators (WDI) 2005. The Bank's annual compendium of economic, social, environmental, business, and technology indicators, the WDI, reports that only 33 countries are on track to reach the 2015 goal of reducing child mortality by two-thirds from its 1990 level. Almost 11 million children a year in developing countries die before the age of five, most from causes that are readily preventable in rich countries. These include respiratory infection, diarrhea, measles and malaria, which together cause 48 percent of child deaths in the developing world. The most difficult challenge is faced by Sub-Saharan Africa, where child mortality has fallen only marginally, from 187 deaths per thousand in 1990 to 171 deaths in 2003. On primary education, 51 countries have achieved the goal of complete enrolment, but over 100 million primary-school-age children remain out of school, almost 60 percent of them girls. This situation endures despite overwhelming evidence that teaching children how to read, write, and count can boost economic growth, arrest the spread of AIDS, and break the cycle of poverty. South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa lag far behind the "Education for All" goal. Turning to income poverty, 400 million people climbed out of extreme poverty (living on less than $1 a day) between 1981 and 2001, reducing the world’s poorest to 1.1 billion people. But in Sub-Saharan Africa, the number of extremely poor almost doubled from 164 million to 313 million. Africa’s lack of progress on the MDGs is largely due to slow growth, complicated by the burdens of disease, famine and armed conflict. By the end of 2003, for example, 15 million children worldwide had lost one or both parents to AIDS, 12 million of them in Africa alone. Similarly, about 85 percent of malaria deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. |

||

| How is Human News different? | Links | Contact Human News | |